A Restock, Reflect, Rethink Three Manifesto by Eleanor Roberts

Introduction

This project has invited me to engage in dialogue with many people (of numerous genders, races, classes, sexualities, ages, and dis/abilities) on the subject of feminism(s) and live art(s). The research journey has offered me great opportunities for sharing space, experience, knowledge, consciousness, art works, and so on, and there have been many unexpected revelations along the way. However, I was particularly surprised, given the context, to find that often people had so much to say on issues of feminisms (a crucial, and indeterminably vast field), that questions of live art fell into the background.[1] This became evident almost immediately, with the very first public event, a Long Table with Lois Weaver on Live Art and Feminism, on 16 October 2013.

Long Table on Live Art and Feminism, 2013

Over a hundred people, spanning three or more generations, discussed many important issues including in/visibility, history-making, daily life, street harassment, concepts of family, theories of re-enactment, race and privilege, education, terminology, sexism in cultural economies, nail art and adornment, ‘beauty’, silence, scattering, drag, age, class, globalisation, and how to maintain communicative networks. Whilst we spoke briefly of a small number of artists and their work – including Hannah O’Shea’s Litany for Women Artists (c. 1976), Suzanne Lacy’s Silver Action (2013) and Marina Abramović’s interrogation of arts production in her early work – discussion of live artists and their particular practices was repeatedly stunted, as one member of the conversation cogently pointed out.[2] Whilst the question of ‘why feminism’ occupied much of the discussion, there seemed to be a tentativeness surrounding the subject of ‘why live art’ – and even more so, a difficulty in speaking on the ‘who’, ‘what’ and ‘why’ of feminist live art. This seemed to reflect, particularly amongst younger women, a frustration and disidentification with feminist terminology, and uncertainty of knowledge on difficult, messy topics that can yield friction and discomfort in heated debate (often with the anxiety that there is always somebody more ‘qualified’ to speak).[3] I never perceived a sense that the timidity about ‘naming’ artists or describing their work came from a lack of interest in historical or contemporary practices; rather, in bodily presence alone, a yearning to know more (and to talk more with each other) was obviously evident. Within the multitudinous and volatile communities of people formed in the moment of meeting in this dialogue, I sensed a deep urgency around questions of the body, and live art as a site of discourse for feminist art.

This Study Room Guide acts as a kind of ‘register’ of feminist live artists (particularly in and around the UK) which can never be comprehensive or complete, but which can at least offer a means, amongst many, of challenging dominant cultural canons sustained by value systems of an imperialist, white supremacist, and capitalist patriarchy lurking in our public institutions. Furthermore, it allows us to remain open to understanding and acting upon ways in which we ourselves might inadvertently perpetuate those structures. The significance of this was particularly apparent in the course of the RRR3 Wikipedia edit-a-thon, where we discovered that many of our most cherished art works and women artists had little or no representation on Wikipedia – even within this most widespread and seemingly ‘open’ web-based platform for sharing knowledge. Whilst many ‘gaps’ in who is represented in the Study Room surely remain, we may at least equip ourselves with the critical (and, in the case of the edit-a-thon, practical) tools to begin a personal journey to determine for ourselves who and what ‘matters’, whose actions speak to us, and how we might move forward in our own processes of self-creation and making work.

However, this process is not simply a means of commemorating the past, but of engaging in the present, and critically, of fashioning our futures. As Nina Arsenault and Tania El Khoury both pointed out in separate conversations within this project, representation alone is not enough (the ‘burden’ of representation may even be felt as a hindrance, particularly for artists from racial or cultural minorities, who are often assumed to singularly ‘represent’ entire communities).[4] We must go beyond representation and address the wider politics and nuanced ways in which live art as a representational strategy is dialogically related to feminisms, and engage in the questions, challenges, and potentiality of the body. Here, theory is not conceived in opposition to practice; rather, they co-exist as part of the same activity or active-ness (indeed, as feminist scholar Geraldine Harris pointed out in one conversation, it is imperative that we challenge what ‘counts’ as theory).[5] This (pseudo-) ‘manifesto’ presents some provocations for personal investigations into some of the issues at stake.

Why Bodies?

Bodies are specific and insist on representation

One feature of the varied landscape of feminist performance and visual arts in the UK in the 1970s was that artists fiercely debated (and disagreed on) how the body might be used, or not used, as a feminist tactic. As Kathy Battista writes in her book, Renegotiating the Body: Feminist Art in 1970s London [P2121], a number of women artists enacted the apparent absence of their own bodies in their work, at least in part as a means of escaping a visual language that was felt to be dominated by men’s images of women’s bodies as (sexual) objects. Conceptual artist Mary Kelly was particularly influential in this respect, after she exhibited a series of object-traces of her experience of motherhood, Post-Partum Document, at the ICA in 1976, which included diary text, analytical drawings relating to her son’s development, and framed nappy stains juxtaposed with feeding charts. Kelly demonstrated that dialogues engaged in questions of women’s bodies – in this instance, of a labouring body – could also take place in forms other than live presence. Similarly, Rose Finn-Kelcey’s work over a lifetime shows how the feminist body can be expressed in live action, but also in ‘vacated’ performance and installation (see, Rose Finn-Kelcey [P2270]).[6]

In contrast to this, as Sonia Boyce argued during the course of this project, for many feminist artists, particularly artists of black and minority ethnicity [BME], to insist on presence and visibility of the body was, and continues to be, a vital form of resistance to the invisibility and silence of those marginalised by the dominance of white, able-bodied, and heteronormative discourses, as represented by patriarchal culture. Many of these issues are discussed by Boyce and others in Documenting Live [D1960 – D1961].[7] Monica Ross’ work also takes forms of intervention in public spaces, for instance in her long-term project acts of memory (2008-2013) [D1303], where Ross invited audiences around the world to join her in memorising and reciting (in many languages) the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, in a ritual designed to catalyse conversation, and reaffirm the presence of humanitarian and egalitarian discourse in (global) public space.

Perhaps most importantly, the specificities of bodies remain crucial; we must resist a static, totalising, and generalising representation of a singular, mythical ‘woman’, and revel in the differences of our constantly changing forms. As part of Fem Fresh – Feminism, Age and Live Art, Welsh-based artist Emily Underwood-Lee tackled this in her performance Titillation (2011-), which presented a post-operative and cancer-marked body in tension with laughter, desire, and the pains and pleasures of looking.

Bodies are intersectional

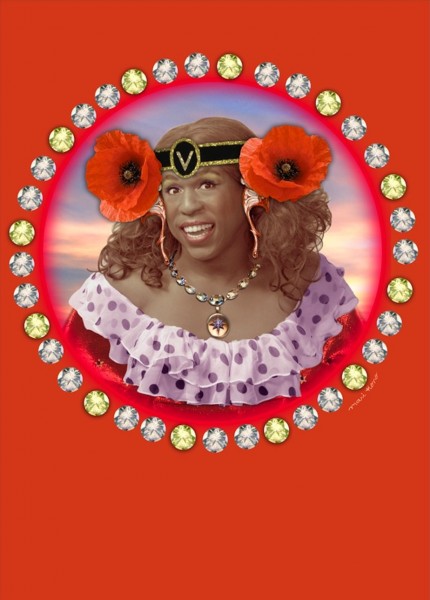

Questions of the body concern gender, race, dis/ability, sexuality, and class. Not only this, bodies are a site of intersection for so many facets of our understanding of the world, not in the least between everyday life and art. This seems an obvious point, but one that is easy to forget, or that tends to remain unspoken in feminist conversation, as I found in my own journey through this project.[8] A discussion of intersectionality, a term coined by scholar and activist Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, can be found in José Muñoz’s book Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics [P0798], which looks at US-based ‘queers of color’ including Carmelita Tropicana and Vaginal Davis. Davis’ form of ‘terrorist drag’ (as conceptualised by Muñoz) is an exercise in boundless simultaneity (man, woman, punk, glamourous, black, blonde, trash, high art), as in her film The White To Be Angry (1999) [D0235].

Women artists utilising their bodies as points of intersection for everyday life and art has an indeterminably lengthy history. In terms of the twentieth-century avant-gardes, I think of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s irrepressible presence, with a shaved and painted head, in the streets of New York in the 1910s, as one possible moment of personal protest – of art altering life, and life altering art. Around the same time, in the UK, Edith Sitwell was also writing and performing poetry-music, appearing in public in outlandish, bejewelled style. A survey of some of the great number of early avant-garde women artists (largely forgotten in history) can be found in Adrien Sina’s book Feminine Futures [P1826]. Later, in the 1970s and beyond, women such as Mary Kelly subverting common conceptions of ‘women’s spheres’ (for instance of domesticity) and presenting them as art, also dialectically altered perceptions and possibilities of everyday living. In the work of UK-based artist Anne Bean, living and working are intertwined in alternative spaces, for instance in the artist-led community at Butler’s Wharf in London in the early 1980s. Working through journeys, sometimes spanning many decades, has influenced Bean’s thinking to the point of self-identifying not simply as artist, but as ‘life artist’ (see Autobituary: Shadow Deeds [P0769], and TAPS: Improvisations with Paul Burwell [P1531]).[9] In more explicit ways, Katherine Araniello’s The Dinner Party (2011) [P2390] draws on autobiographical experience of disability and remembered social encounters with ‘guests from hell’. Araniello’s work, like that of Vaginal Davis, can be both raging and deeply funny.

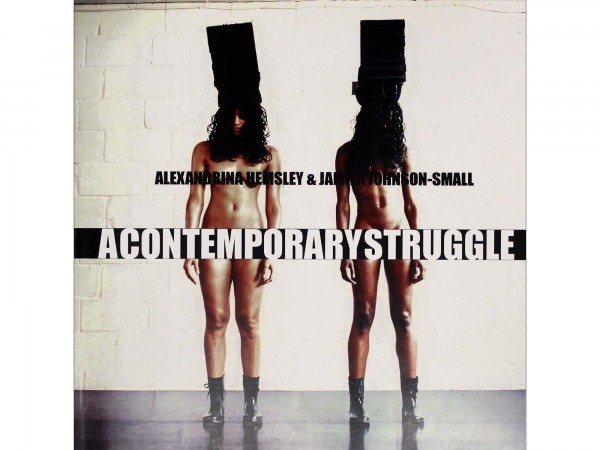

Bodies give us access to knowledge and the tools to create other languages

Bodies in performance refuse the (fundamentally patriarchal) notion of the Cartesian split, by which were told that our minds are distinct from the mere ‘vessels’ of our bodies. As Colette Conroy points out in her book, Theatre & The Body [P1389], where thoughts become actions, corporeality and sensations of the body must be acknowledged as forms of understanding, and enabling knowledge. The body may be a medium of culture, but it also creates culture, and offers feminist artists the means to express and create new non-verbal languages, where language as a dominant form is so often designed and controlled by men to reaffirm patriarchal privileges (an obvious example being that the naming of ‘Mr’ and ‘Miss’ or ‘Mrs’ denotes the sexual ‘availability’ of women, but not of men).[10] For instance, we might think of artists working with dance such as Yvonne Rainer in the 1960s (see Being Watched: Yvonne Rainer in the 1960s [P1771]), or Project O in present time (see A Contemporary Struggle [P2240]), as being involved in expressing ideas through language that intersects with, but also exists outside of, verbal-textual communication. In her more visual-arts based practice, Carolee Schneemann is also highly influential in creating artistic languages which traverse bodily senses such as sight, sound, sensation and smell (see, Imaging Her Erotics [P0346]). In the UK today, with music and moustachioed drag, Verity Susman challenges what she brilliantly calls the ‘Philip Glass Ceiling’.

Bodies are sites of self-fashioning

Historically and today, to varying degrees in specific contexts, women’s positions in patriarchal societies have been led or limited by their bodies, and assumed notions of (hetero) sexual and reproductive ‘functionality’. For example, performance-activist collective Speaking of I.M.E.L.D.A. tackle the ongoing struggle for Irish women forced to travel to England to obtain access to legal abortion.[11] For some women, the desire to escape their own bodies and the confines of prescribed ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ altogether creeps through, but is perhaps ultimately futile. Feminist performance offers a means of wresting control of the body from a totalising, unifying understanding of ‘the female’, into something multiple, changeable, and subversively pleasurable. This process is made particularly visible in ‘confessional’ monologues, such as those performed by Holly Hughes and Karen Finley, both of which feature in Angry Women [P0144], an early-1990s zine-style publication which focuses on (though is not limited to) influential artists in North America.

In Judith/Jack Halberstam’s notion of ‘queer time’, we have the discursive tools to resist assaults of patriarchy by self-fashioning forms that are not reproductive, long-lived, or categorisable, and which exist in repetitive (perpetually ‘teenage’) time.[12] In The Queer Art of Failure [P2232], Halberstam sets out to critique notions of ‘productivity’ in an age of hyper-capitalism. Similar conceptions of time are visible in Oreet Ashery’s ‘feminist cut-ups’ and work across media performing multiple tempos, times, places, selves, egos – such as that of a Jewish orthodox man (see Oh Jerusalem [DB0002]). We also see this conception of self-fashioned ‘cut and paste’ bodies very explicitly represented in Linder’s work in the 1970s (See Linder [P2222]), which mutated, modified, and subverted magazine and advertising imagery.

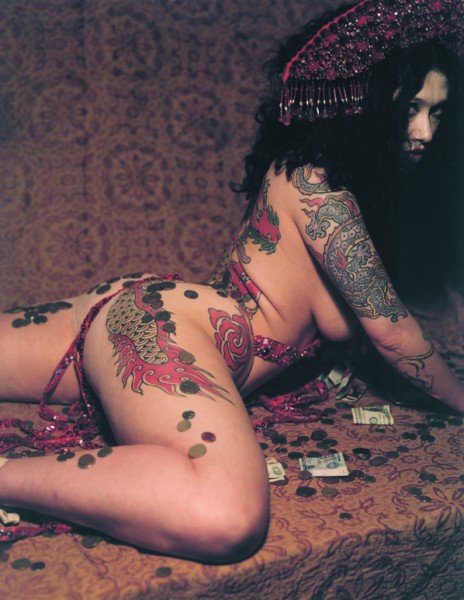

Feminist artists have also engaged in the self-fashioning of their own bodies through painful interventions. For instance, in France since the early 1970s Gina Pane challenged herself and spectators in violent political climates by performing actions designed to engender pain and injury to her own body (see Gina Pane [P0281]). Since 1990 Orlan, another French artist, has invited audiences to witness the gradual sculpting of her body through a series of plastic surgeries (see Carnal Art: Orlan’s Refacing [P0732]). Emerging later in the UK, Kira O’Reilly has performed dangerous or risky works such as her blood-letting ritual Wet Cup [DB0040] (2011), and Marisa Carnesky has explored body modification and tattoo culture, as in Jewess Tatooess [V0315 / EV0315] (1999).

Bodies are pleasurable

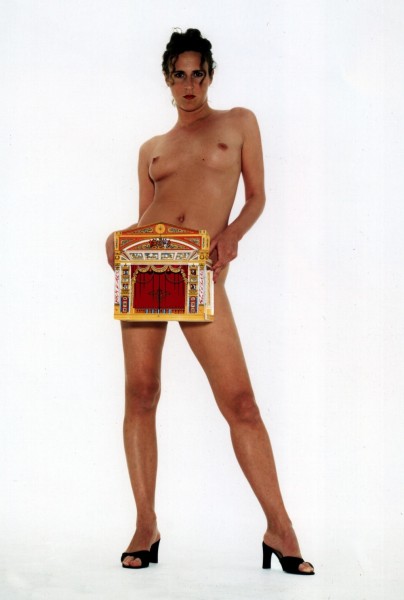

Where we so often experience our bodies as a source of pain, there is also a radical potential in the pleasures of the self-fashioned body as a desiring and desired subject. For instance, in ageist society, Tammy Whynot (the self-fashioned alter-ego of Lois Weaver) in What Tammy Needs to Know… About Getting Old and Having Sex (D1071) engaged groups of older people in conversation on often ‘taboo’ subject, in resistance to pre-determined ‘norms’ and mechanisation of age-related un/productivities. In her book The Explicit Body in Performance [P0124], Rebecca Schneider discusses enactments of sexual agency and desire in performance (such as that of Spiderwoman, Karen Finley, Ana Mendieta, and Robbie McCauley). In the UK in the 1970s, Cosey Fanni Tutti’s magazine actions converged glamour and pornographic modelling with high art spaces (see Cosey Complex [P1910]), as US-based artist Annie Sprinkle did with live sex in the 1990s (see Herstory of Porn [D0774]).

Lois Weaver, image courtesy of artist

The potential of desire also takes less sexual forms for feminist artists. For instance, bell hooks argues that ‘yearning’ as a consciousness and political force cuts across boundaries of race, class, gender and sexuality. Bodies sharing space have the potential to constitute a common ground of daily life, art, intellect and understanding through which we can construct shared empathies and pleasures that ‘promote recognition of common commitments and serve as a base for solidarity and coaltion’.[13] Shared laughter is also a tool for subversion, as I saw in Liz Aggiss’ piece Cut with Kitchen Knife: a bit of slap and tickle (2014), and Marcia Farquhar’s Art Tips for Girls – both incredibly funny episodes in Fem Fresh – Feminism, Age and Live Art. In the UK since the early 1970s, Bobby Baker’s performance work has exemplified this refusal either to be contained by seriousness, or to dilute the political energy of laughter (see, Bobby Baker: Redeeming Features of Everyday Life [P1051]), even in tension with contexts of serious feminist debate.[14] Ursula Martinez, another London-based artist, plays with the ‘seriousness’ of female nudity through cabaret and spoken word forms; for instance, in her recent show My Stories, Your Emails (2010-) a strip-tease reveals Martinez’s naked bottom, but also an errant piece of clinging toilet tissue.[15]

Bodies are indeterminate and foreground active interpretation

Judith Butler argues that gender is manifested through ritualised repetitions of ‘sex’ (female, male) across time.[16] Our ‘sex’ is not a static condition of ‘who we are’, or what we ‘have’, but an effect of power structures, by which we become culturally ‘intelligible’ (as a ‘woman’ or otherwise). Raised consciousness and understanding of our position as performers allows us to trouble this cultural ‘intelligibility’, whereby the self-fashioning of our bodies might allow us to rethink and resist what are presented to us as pre-determined categories. In the UK, since the 1990s, David Hoyle has persuasively advocated a refusal to be contained by ‘sex’, and has been consistent in his vehement and hilarious indictments against the ‘men’ (macho, imperialist) in authority who are our enemies (see Magazine: 10 Live Performance Essays by David Hoyle [D1660]).

Bodies in performance can make visible the process of construction and transformation of ‘becoming’ women or otherwise. Lucy Hutson’s recent work If You Want Bigger Yorkshire Puddings You Need A Bigger Tin [D2053] (2013-) presents an autobiographical journey of ongoing gender formation, negotiating a (never-ending) path through family and oral history, lived experience, domestic finesse, and medical dictum. In Hutson’s work, arguably as in all performance to varying degrees, we never simply find the answer (‘now I know what woman really is’), on the contrary, we are engaged in an active spectatorship and ongoing processes of creating discourse, possibilities, and space for women or those in fluid gender modes in all their differences and specificities.

Bodies sharing space creates discourses and breaks silence

The strength of this last (but by no means final) point has been felt throughout this project in the various conversations I’ve been fortunate enough to be a part of. As Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, and others have said, discursive silence is the most violent and dangerous place to fall into – and which, through uncertainty, frustration, and discomfort, must be resisted by feminists at all costs.

[1] By ‘questions of live art’ I mean conversations including but not limited to definitions, histories, artists, form, content, how and what specific pieces provoke or point out, how and why live art can be used by feminists for making work and opening dialogue, and so on.

[2] Growing restlessness and realisation of what was ‘missing’ from the conversation became catalysed at one point after a young man (naively) asked the room to collectively explain what feminism is, and why ‘women’ (in general) are ‘critical’ of Marina Abramović. Later, Jennifer Doyle broke the relative silence on naming feminist artists by pointing out the inherent sexism of allowing feminist live artists and their practices to remain unspoken, kick-starting a survey by bringing Kira O’Reilly, Vaginal Davis, and Lois Weaver ‘onto the table’.

[3] The term ‘disidentification’ is borrowed from José Esteban Muñoz. For Muñoz, it allows a means of describing ‘survival’ strategies of ‘queers of color’ in renegotiating the ‘white ideal’ and (imperialist, capitalist, patriarchal) normativity by utilising marginality, ugliness, or ‘damaged’ stereotypes or politics as means of self-creation. Here, for my purposes, I am altering the meaning slightly to focus on what Muñoz suggests to me about a desire that is troubled but also troubling, where he writes, ‘We desire it but desire it with a difference’. We need feminisms to be perpetually engaged in self-criticism, to always be open in identifying and dismantling our own ‘establishment’ politics, and to rearticulate how we define feminism and how it suits our various and specific needs. See, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), p. 15 [P0798].

[4] Tania El Khoury spoke eloquently on this in relation to audience responses to her work Maybe if you choreograph me you will feel better (2011-2012), in a ‘Diversity Now’ Coffee Table with Lois Weaver as part of this project. Nina Arsenault also discussed this at the first Long Table on Live Art and Feminism (16 October 2013) in an introductory talk alongside Poppy Jackson on their aGender residency at ]performance s p a c e[.

[5] Harris remarked on this issue of theory in A Cocktail Seminar on Feminism, Live Art, Archives and the Academy at Queen Mary, University of London, 9 June 2014.

[6] A Wikipedia page was created for Rose Finn-Kelcey in the Wikipedia edit-a-thon as part of this project.

[7] Sonia Boyce discussed this matter in an ‘Early Days’ Coffee Table discussion with Lois Weaver on 2 May 2014. Boyce cited the influence of artists and events such as the feminist collective Fenix (including Monica Ross and Kate Walker), Susan Lewis’ performance Ladies Falling at ICA (c.1994), meeting Lois Keidan and Catherine Ugwu, and coming into contact with the work of Nina Edge, Lesley Sanderson, Yeu Lai Meu, Frank Chickens and Kazuko Hohki in the 1990s. Formerly, Boyce co-directed AAVAA (African and Asian Visual Artist Archive) at University of East London, which, like the related Documenting Live project, was designed to create discourse about contemporary work by African and Asian artists in the UK such as Yinka Shonibare, Zarina Bhimji, and Susan Lewis.

[8] In June 2014, as part of this project, I presented at A Cocktail Seminar on Feminism, Live Art, Archives and the Academy, which consisted of a public panel discussion with feminist academics, hosted by Lois Weaver. Whilst I felt (perhaps with the assistance of fabulous cocktails) the conversation to be exciting, thought-provoking, and varied, talking with a group of participants afterwards made me re-think my (relatively) comfortable position of self-affirmation. They highlighted to me their feelings of disappointment and uncertainty in that the all-white composition of those demarcated as ‘academics’ further marginalised issues such as race and class, and assumed a ‘neutral’ position of educated whiteness. Whilst this oversight was, in part, a reflection of the institutional whiteness of Queen Mary, University of London Drama department, it was also unacceptable and left unacknowledged at the time, and I am grateful to those I spoke with for making room for self-criticism on this matter.

[9] Anne Bean referred to a possible category of self-identification as being ‘life artist’ in the ‘Early Days’ Coffee Table discussion with Lois Weaver on 2 May 2014.

[10] Dale Spender, Man Made Language, 2nd edition (London and New York: Pandora, 1985), p. 27.

[11] One action took place on 8 March 2014 at the London Irish Centre. See, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dr1z_aCKoOQ.

[12] Judith Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York and London: New York University Press, 2005).

[13] bell hooks, ‘Postmodern Blackness’, in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1990), pp. 23-31. Accessible online at <http://www.mariabuszek.com/kcai/PoMoSeminar/Readings/hooksPoMoBlckness.pdf>

[14] Other UK-based artists I could mention here, in harnessing humour as a disruptive (feminist) force since the 1970s, include Silvia Ziranek, Carlyle Reedy, and theatre collective Cunning Stunts.

[15] It might be worth pointing out that Martinez has an ambivalent or complicated relationship to feminism, though I read her act as holding feminist possibility.

[16] See Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’ (London: Routledge, 1993), pp. 1-2.